Stories from Redeployment Worksites

Join us on a journey through the history of redeployment worksites and the hut villages that grew up around them. The online exhibition is divided into three different sections. You can take a virtual tour to peek inside the huts, jump into the daily life of the hut village with workman Hugo Havu through acted scenes and deepen your knowledge through texts about redeployment worksites and relief work.

The walls of the hut village contain stories of a time when tens of thousands of men and thousands of women were sent to remote areas to perform relief work. The worksites could be located hundreds of kilometres away, far from home. The trip to the unknown location was free.

Virtual

tour

Here you can take a 360-virtual tour of the hut village

The virtual tour allows you to easily navigate from one hotspot to the next. Click the white circle on the screen to move to the next spot in the tour. Some of the huts also open up to the visitor through the hotspots. You can also move your mouse or finger on the screen to reveal outlines. Click on them to find much more in-depth content.

Jump into the story

Experience the daily life of the redeployment worksites and hut villages through acted scenes. Workman Hugo Havu will take you on a journey where you meet workers returning from work, spending their day off, and writing a letter home. You will also see the worksite office and even hear about romance.

Welcome to the hut village

Far from home

Payday

A worker’s day off

In the blacksmith’s forge

Of food and love

VIDEO TEAM

Screenplay: Noora Kytöharju

Filming: Esa Alhola and Mikko Alhola

Editing: Esa Alhola

Soundtrack: Pasi Salmi

ACTORS

Hugo Havu: Mika Eerola

Helga Nieminen: Noora Koski

Taavetti Tuppurainen: Mauri Hakanen

Emil Lahikainen: Sakarias Koivisto

Elli Jokinen: Elina Mäkinen

Akseli Heikkilä: Jouni Iivonen

Sulo Koponen: Juhani Karppila

WELCOME TO THE SHOVEL LINE

Relief work, or the so-called “shovel line”, was the Finnish employment policy’s most important method for tackling unemployment after World War II. At that time, the options were scarce if you were unemployed and wanted to provide for your family. The labour authorities decided whether to send someone for relief work. If you declined, you lost your right to relief work that year.

Civil engineering was the biggest employer of the unemployed. One could say that a significant part of Finland’s main road network has been constructed as relief work. Forest work, canal construction, and airport construction were also partly performed as relief work. The unemployed also constructed railways, apartment buildings, and hospitals. They practised forestry, restored log floating channels and waterways, and maintained parks and playing fields.

The period starts from the late 1940s, after World War II, and ends in the early 1970s when new legislation provided unemployment benefits.

Civil engineering was the biggest employer of the unemployed. One could say that a significant part of Finland’s main road network has been constructed as relief work.

THE FIRST REDEPLOYMENT WORKSITES

Before the war, it was called ‘relief work’, after the war, ‘unemployment work’, and from the 1950s onwards, ‘employment work’. For an unemployed person, the name did not matter, because it was about the same thing. Relief work was first organized for the unemployed in the late 1800s during the years of famine. Before World War II, the unemployed worked at canal construction sites, and after the war, they were reconstructing Lapland which had been destroyed in the war. The first redeployment worksites with hut villages were also created in Lapland.

Right after the war, there was some unemployment in Finland. The situation settled at first, but by the end of the 1940s, the employment situation started to rapidly decline. In December 1949, nearly 60,000 people had registered as unemployed. Unemployment continued to rise in the 1950s.

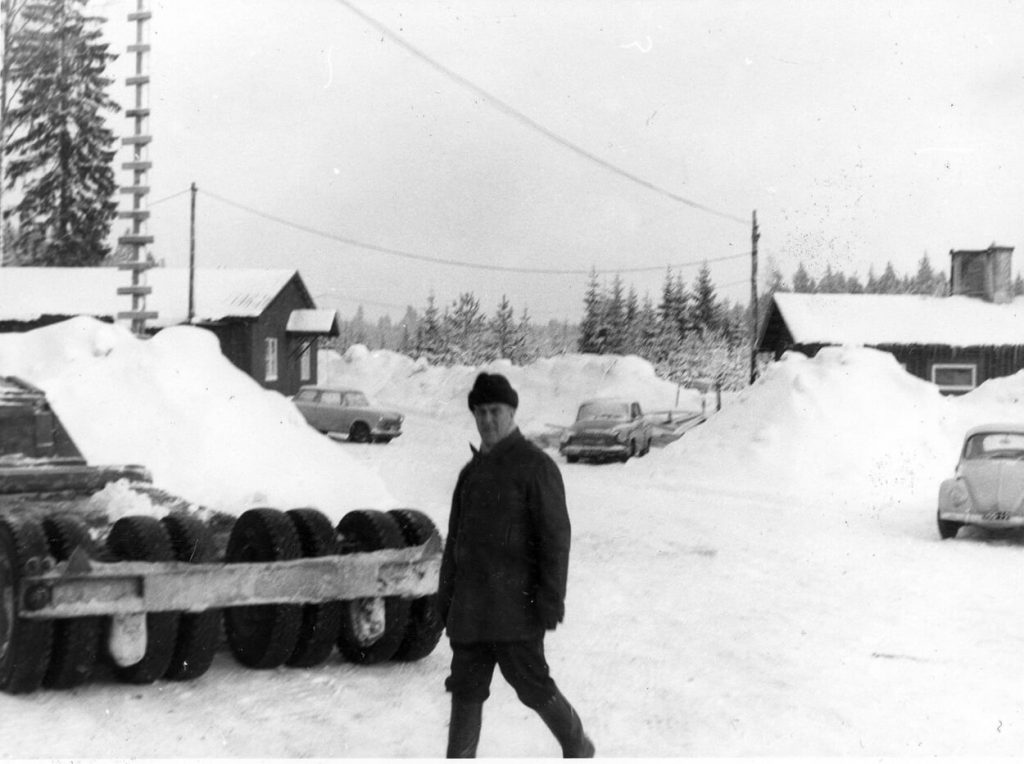

Road construction was well suited for relief work. The areas with the highest unemployment rates were in Eastern and Northern Finland. The traffic-related need for road work was in Southern Finland. It was decided that the unemployed would be transferred to Southern Finland for road construction work. In the winter of 1958–59, there were over 50,000 unemployed people working on redeployment worksites, over 16,000 of whom were living in the hut villages.

It was decided that the unemployed would be transferred to Southern Finland for road construction work. At most, there were over 50,000 unemployed people working on redeployment worksites, over 16,000 of whom were living in the hut villages.

Leaving home was something that was talked about bitterly in the redeployment site huts. The war had just ended, so the standard of living was not very high. The housing conditions of the poor in Northern and Eastern Finland were not much different from those of the redeployment worksites, so there were no complaints as such. The hardest part was getting used to the cramped quarters and adapting to the ways of dozens of strangers.

UNEMPLOYMENT WORKERS

Who were they?

The largest group of people in relief work were small farmers from the countryside. Many of them were evacuees or had served on the front. After the war, over 100,000 small homesteads were established in Finland, with insufficient land to provide for the family in winter. Land was given to evacuees and veterans.

During the worst unemployment periods in the late 1950s, there were over 30,000 registered unemployed farmers. Relief work was mainly manual labour. Work on the roads, land, and forest required strength. You couldn’t do the work if you weren’t in good shape.

The labourers on construction sites were not unskilled, as many tasks on roadworks and construction sites require training and practical learning. In addition, young unemployed people were trained as machine operators, maintenance repairers, crusher operators, clerks and surveyors.

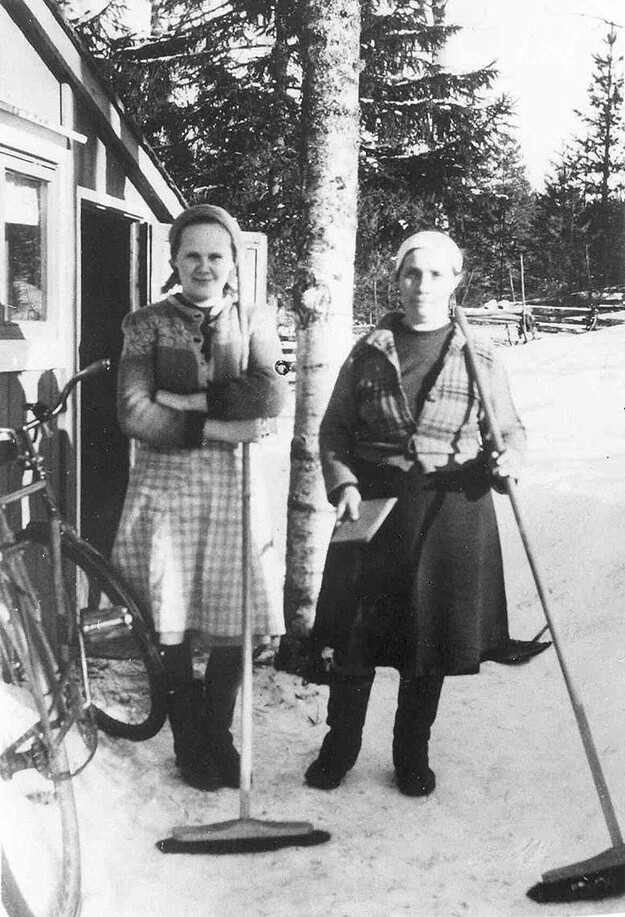

Women in relief work

Sending women to redeployment worksites was discussed in the mid-1950s. The employment committee thought about it and decided that volunteer women could be sent to redeployment sites. The share of women at the sites remained fairly small. They were mainly hired for levelling the slopes, which were the edges between the roadside and the ditch. Most of them were local and commuted to work from their homes. There was also an experiment with women staying in a hut village. However, the experiment was discontinued as it was ultimately deemed inappropriate.

In addition, site canteen staff and cleaners tended to be women. They were usually recruited locally. If they could not be recruited locally, they could be housed in their own huts in the hut village.

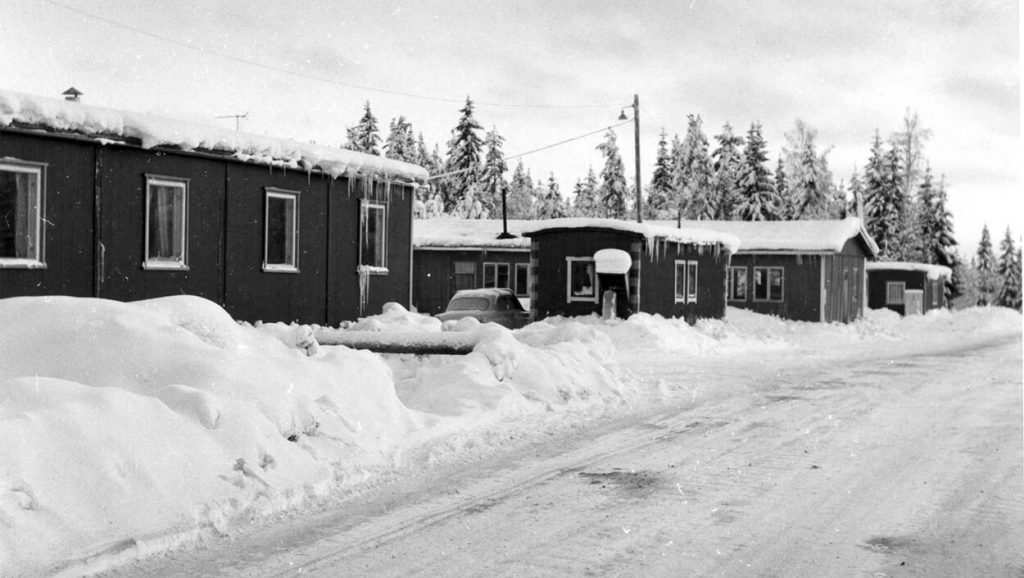

LIVING IN THE HUT VILLAGE

The sites were often far from home. The hut villages in the redeployment workplaces were born out of the need to accommodate those who came from further afield. The hut village could be like a little town. There were all kinds of people: in addition to the actual road construction workers and supervisors, there were office staff, caterers, heaters, hut men, sauna heaters, cleaners, woodchoppers, washers, and even shoemakers, water distributors, and other hut village maintenance staff.

As there were different worksites, the huts came in every size and type. According to the regulation of 1945, there had to be at least 5m³ of space for every worker. In 1966, a new regulation was given, providing at least 7m³ of space. Later, the roads and waterways administration expressed a wish that the hutted accommodation at state worksites would provide a space of 10m³ for each worker.

Mobile home

The house trailer for 8 people in the picture is about 2 metres wide. These were generally used to accommodate site supervisors. The workers stayed in huts occupied by dozens of men. This trailer model was developed in the early 1950s. The bases were the chassis of trucks to be scrapped. The house trailers had a central heating system. In the early days, the huts were heated with brick stoves and tin stoves. Before central heating systems, temperature regulation was difficult. On cold winter nights, the temperature on the room floor was only a few degrees Celsius.

The men slept in bunk beds with paper or fabric mattress covers, pillowcases, and blankets. The mattresses were filled with straw or hay. The furniture consisted of a small table and a few stools. There were hooks and nails on the walls for hanging different things. There were clothes, backpacks and lunch bags hanging in each one. The huts were also often bleak and dirty. The ventilation was poor and the cigarettes smoked inside had stained the walls yellow. The site management tried to pay attention to cleanliness. However, some of the men were rather untidy and their manners often dictated the look of the whole hut.

Toilets

According to instructions, toilets were to be placed in the hut villages on the north or east side and in a shadowy spot. This was provided in the maintenance regulation passed in 1945. There were all kinds of difficulties in the everyday life of the hut villages, and sometimes even rudimentary manners were forgotten. The maintenance directors are reported to have been thinking about how to get every man to walk all the way up to the toilet when they had to go.

Smell

Relief work was generally performed in the winter when hut windows and doors had to be kept shut. Airing out the huts wasn’t possible because the heat would have escaped. The characteristic smell of the huts has been described as typical for every hut. It was created when tobacco, sweat, dirt, and sour rye bread mixed. The rooms were often cramped, and many workers slept in each room. Wet, sweaty, greasy, and muddy clothes were dried wherever there was space.

Relief work was generally performed in the winter when hut windows and doors had to be kept shut. Airing out the huts wasn’t possible because the heat would have escaped. The characteristic smell of the huts has been described as typical for every hut.

Washing

The sauna was the most important place for maintaining cleanliness. It was self-evident that there would be a sauna at every redeployment worksite. If, for some reason, there wasn’t a sauna at a smaller worksite, the men were transported to the nearest one to have a sauna. At first, the sauna was heated up once a week, on Wednesdays or Saturdays. Later, the number of sauna days was increased. New huts also came with shower rooms. However, not all of them were replaced at once, and for a long time there were still some huts that lacked any washing facilities at all. The site management arranged for washing water to be delivered to them from time to time.

Leisure

Maintenance regulations provided that hobby activities should be available at the worksites. The supervisors had to acquire various types of sports equipment and games. Novuss, chess, checkers, and darts were common games. The men’s local newspapers were also subscribed to. When radios became more common, the “Saturday night’s requests” was a popular programme.

Partying

Saturdays were only half days. After work, people went home or prepared to spend the weekend in the hut village. The payday was twice a month. Usually Saturdays. Some of the money was spent on alcohol. For public order, the weekends after the first paydays were usually the worst. Troublemakers were sent away from the worksite, and after that, order was restored.

The sauna was the most important place for maintaining cleanliness. It was self-evident that there would be a sauna at every redeployment worksite. If, for some reason, there wasn’t a sauna at a smaller worksite, the men were transported to the nearest one to have a sauna.

Eetu Happonen worked as a hut warmer and Yrjö Karvinen drove firewood with his horse. He also delivered water to the canteen and the huts and washing water to the sauna. The men sitting at a table in a hut for 20 persons. The photo was taken in 1956. Photo: Kalevi Pakarinen © Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency – Mobilia

AT THE WORKSITE

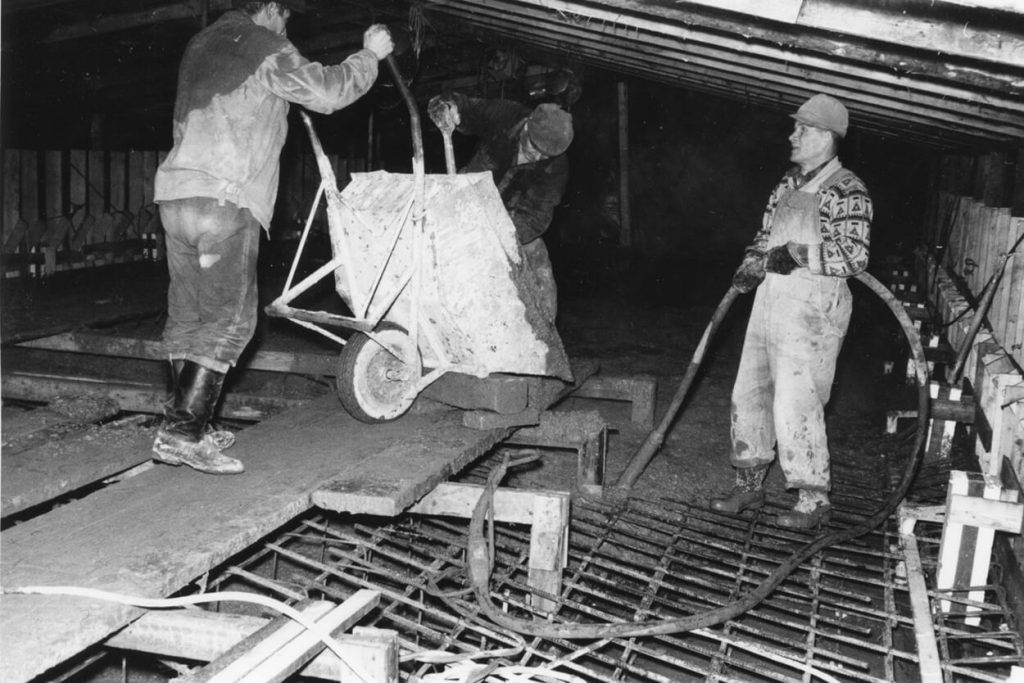

Everyone can imagine what it was like to dig the frozen ground with a shovel or scoop gravel onto a truck in freezing cold. To work outdoors for hours on end with a shovel, a bar, or an axe. Road construction was expensive and difficult in the winter, but the unemployment rates were the highest then, and relief work was needed the most.

Machines and people

Before machines were available, earthmoving was performed manually. A group of men shovelled the load onto a horse carriage or a truck. In the late 1940s, there were fairly few trucks, which meant that usually the load was pulled by a horse. The first noticeable period of mechanization took place in the early 1950s. Machines helped to perform the work quicker and better.

By the mid-1950s, the roads and waterways administration had a fleet of 2,600 trucks, over 150 excavators, and some 150 bulldozers. As the number of machines increased, there were also more specialists and fewer general labourers sent in by the employment authorities. For this reason, the government restricted the use of machinery at worksites.

Towards the end

Many worksites were started during the periods of high unemployment rates in the 1950s. Roads were constructed, but finishing and maintenance work suffered. Essential sections of the main road network were constructed as relief and unemployment work. In the 1960s, the employment policy started to change. Mechanization had also begun. Freeways were wanted, and they couldn’t be constructed with manual labour alone. Road construction as relief work was expensive and difficult to coordinate. The shovel line and the conditions at the redeployment sites received an increasing amount of criticism. By the 1960s, they were regarded as an unethical policy.

The shovel line had been criticised throughout its existence. The redeployment worksites and their conditions were publicly criticised. A change was coming and relief work was thought to be the wrong policy. It was felt that the focus should be on economic growth and business opportunities. More actual work appropriations were allocated to the projects. The same men went to work on the road construction sites, but they were no longer relief workers. They were now roadworkers.

UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFIT

General monetary compensation was decreed as early as the late 1950s and early 1960s. It was extended to concern everyone. However, no money was paid, because the municipalities considered that there was a lot of work to be done. The unemployment benefit was completely reformed in the early 1970s. New regulations in 1971 put an end to relief work and redeployment worksites. The monetary compensation applied to all unemployed who were without a job through no fault of their own. Employees also received occupational immunity.